The juxtaposition of affordable housing and job growth:

Things have changed in the housing landscape over the past few decades, but few of us stop to examine why.

Builders and developers simply no longer build enough units to meet demand and keep prices affordable for most Americans, according to Scott Cox in a series of articles in BUILDER Magazine. “The house price-to-median household income ratio in this country was 2.2:1 until the 1970s. Over time the average rose to 2.8:1,” says Cox. “We’re now at 3.4:1.” He goes on to say that in high growth areas the figures are much higher – as much as 10:1. Concerns include rising mortgage rates, making it more critical than ever that sufficient housing is built to keep supply and demand in balance.

So how did we get here? Cox cites a pattern developing across the country where job growth in large metro areas draw employees from other parts of the country. “Initially, the growth is cheered fairly universally. If the job growth is taking place after a down period, the newly employed are filling up vacant units and there are few objections.” Then traffic begins to increase, and growth benefits diminish except for those with their own homes and stable jobs. Nowadays when new apartment projects or townhouse developments are proposed near existing single-family neighborhoods, residents often protest against additional growth. Even when an older neighborhood gets a spark of gentrification, rents begin to rise to levels many find difficult to afford.

“Unfortunately, the protests do not focus on the root cause – job growth,” says Cox. “All of the attention is focused on limiting housing as if somehow that will eliminate the traffic and school problems (or the price pressure on existing neighborhoods). The equation is simple – jobs become available, people fill them and those people need a place to live.” He goes on to say that housing does not drive job growth – it responds to it. “Yet housing ends up in the crosshairs,” he says. Of course, no one will say they are anti-job growth. It’s chicken-and-the-egg kind of thing. Cox asks, however, “How can we have economic development groups and incentives for employers and be against new housing? The only way this makes sense is if your goal is to raise the price of your own home and exclude others from the housing market. Sadly, this is the motivation of many, hidden behind ‘maintaining our community’s character’ statements.”

It wasn’t long ago when growth changes were considered progress. Residents not only wanted, but expected their city to change over time. Cox says, “Infrastructure was built by government to facilitate growth, much of which happened by expanding the metropolitan regions. But then tax revolts and shifting budget priorities limited available revenues to governments, who then chose to allocate fewer funds to roads, sewers, water, etc. And environmentalists fought bitterly against the traditional suburban growth model. Growth became a dirty word, at least as it relates to residential development.”

Now we are evidently at the point where working people with decent jobs are spending 40%-50% of their incomes on housing, while young professionals in high-cost metros find it difficult to afford an apartment.

So what can be done? “While we cannot look into the heart of every homeowner who has protested against a new project in their city, we can say unequivocally that homeowners’ active stifling of housing growth is systematically denying the American dream to young people across the country,” says Cox, who goes on to say how it’s one of the single greatest contributors to the growing income inequality in this country.

The challenge to builders is to acknowledge their choices as well as the consequences of those choices. Little job growth causes little housing growth. Nothing about a neighborhood changes and young people move away since opportunities for them are not being created. Residents won’t have to worry about an apartment building being built down the street, either.

Then there is the scenario of good job growth with little housing growth — a path being followed by most high-growth areas. This snapshot encompasses a growing income inequality and polarization of the community. Homeowners prosper through rising prices, knowing the only way they can cash in on their equity is to sell and leave the area, and those seeking affordable housing are forced to seek it farther and away from their jobs.

The third scenario is, of course, good job growth along with good housing growth. This is where the character of the community evolves, young people thrive as they have both opportunities to build careers and find affordable housing, and in the process become attached to their community. While change may not always be comfortable for locals, earning a decent living while occupying a decent home seems to be a good trade for that discomfort. “Houses are where jobs go to sleep at night,” says Cox.

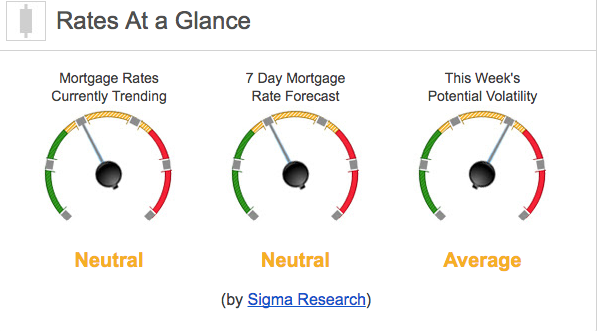

Rates Currently Trending: Neutral

Mortgage rates are trending sideways this morning. Last week the MBS market improved by +9bps. This was not enough to move rates lower last week. There was moderate mortgage rate volatility last week.